24 Jan

2017

How to Avoid Pitfalls in Family History Discovery and Sharing

Avoid Pitfalls

In Family History Discovery and Sharing

In your family history detective work you cannot expect to be perfect, but you should strive to avoid pitfalls. There are few pitfalls more gut wrenching than spending time in discovery only to have your findings dashed by others. This article is written to help you avoid pitfalls that result in you being dashed. Let’s consider three scenarios.

In the first scenario, you share your findings online and suddenly you find that you have been cut off from that newly discovered family tree. When you question the online tree owner, s/he informs you that you could not possible related to them because of xyz.

In another, you make a family discovery that uncovers a deep dark hidden secret and now a family member (or group of family members) is upset with you. “That was well hidden. Why did you dig that up?” Remember Ben Aflec on PBS. There are some family stories that have been carefully hidden, deliberately not talked about, and some people will not appreciate the uncovering of those stories.

Finally, there is the scenario where the family discovery is just plain wrong. You have published as fact – family lore or speculation.

The joy and passion of family history discovery is an adventure filled with much passion. We cannot let our passions get the best of us. In this series I will ask three common questions posed by the beginner family history detective; then I’ll give the answer. So let’s get started.

Part one

Q. Why have I just been ‘unfriended’ by my family history community collaborator(s)?

Let’s start with the first pitfall I mentioned – you have your family tree on MyHeritage or join your tree or share your findings on Ancestry or some family history site and suddenly you find that your Record Match or hint leaf has vanished and you have been cut off from that newly discovered family tree. When you question the move, the tree owner informs you that you could not possible related to them because [you fill in the blank].

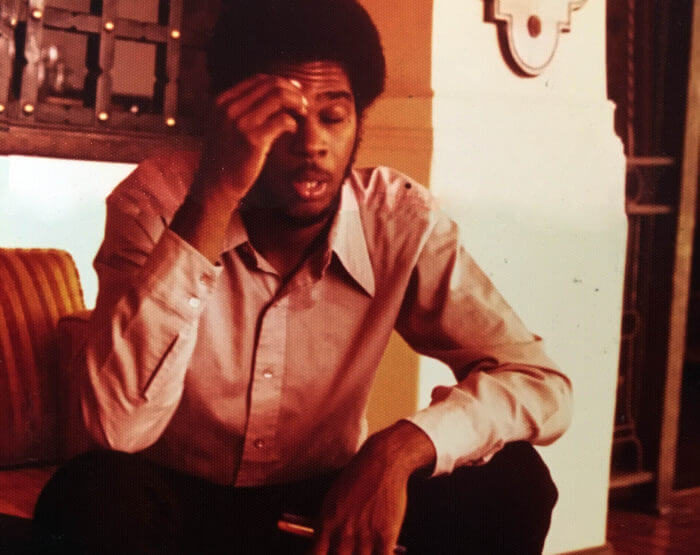

This just recently happened to a friend of mine. For years, he has been tracing his family linage and recently came across a branch of his father’s family that seemed to shed a lot of light and add validity to some of the family lore. He is African American with an Italian surname. He found an ancestor with the correct name. The ancestors brothers and sisters were all there – with the correct numbers and names. Then he noticed there was a relative he had not known of so he began to search this branch out. Not long after making a connection and adding a part of this new tree to his own, he logs on one day to discover the link is broken and he no longer has access to this info. The trees owner informed him that since he was African American there was obviously a mistake and that there was no possible way that the two of them were in any way related. He went on to tell my friend that he should immediate cease telling people of such a connection as it only served to disparage the good name of his ancestors.

So how do you avoid pitfalls like this one?

A. You did not own your own work and verify.

Two ways to avoid “talking to the hand” of your family history community collaborator(s)

First, own your research data. Download records to your own computer for safe keeping and VERIFY!!!

You see, this is the problem with online family research and collaboration – copying and sharing other people’s research.

Always take ownership of the work. Make it your own. Always keep a local copy of all your work. Backup your records often and always keep copies of your family history documents. When I find new info, I add that info to my own being careful to note the source. There is a really good reason to do this. As my friend discovered – when you do not own the data it can disappear. The info may actually be correct, you will want to know the newly discovered family connections so that you can build on it (if the sources are there and verified).

But, if this data proves to be false – you will want to be able to remove it from your research data and also you will want to pay attention to the similarities or errors that caused the mistake. Study the ways things went wrong so that you learn to make better connections as you continue. Just because the Phyllis White you have found seems to fit the bill does not necessarily mean that she is your Phyllis White.

Second, always check sources.

Always wait until the sources prove a connection to a known relative before moving on. This can stop you from researching ‘the wrong’ family. It may well be a key in highlighting folks already in your own research that should not be there. Heed this advice from Ancestry – ALWAYS “Keep calm and cite your sources! Always document where you have found your information. Your research is your legacy to future generations who research your family tree. One simple mistake or un-sourced addition to your tree could cause others to make assumptions and in turn make mistakes in their own research.”

Remember the goal here is to avoid pitfalls as you pull together the narrative of your family stories. In closing I’d like to quote from a good article on the FamilySearch.org website.

Rookies avoid discussing contradictory evidence

The inexperienced may reject sources that show the ancestor’s name spelled differently than expected. Even the use of a previously unknown nick name or a middle name may be rejected without adequate study to understand their usage. They may suppress sources that disagree with their point of view by not citing them. And if they do cite such sources, they may fail to acknowledge the contradictions which need further clarification.

Consequences: Overlooked sources, under used sources, or poor evaluation of sources. This can lead to conclusions based on less than all the best available evidence.

Experienced researchers embrace contradictions and discrepancies by openly acknowledging them, analyzing them, and explaining what accounts for them; it is all a part of the research process. They strive to expose these kinds of problems, understand them, and explain them in order to more fully understand all they can about a research problem. Knowing and admitting the weaknesses of a case leads to better analysis. It keeps one open to the discovery of future evidence that may invalidate or verify their existing conclusions.